The timing of this plaque’s unveiling coincided with the bicentenary of his first voyage, with the plaque containing the quote: “To strive, to seek, to find and not to yield”. Although JAMES COOK is written in capital letters, the inscription very much heralds the people of Whitby (“ This plaque is to commemorate the men who built the Whitby ships, Endeavor, Resolution, Adventure, Discovery”), as well as the “men who sailed with him”. This umbilical connection between the exploits (and exploitative activities) of Captain Cook and the people of Whitby is further underlined on a plaque that was added in 1968. Whatever one might think about James Cook – rampant colonialist or innocent navigator – the inscription implicates the whole town of Whitby.

James Cook wasn’t born there (he was born in the village of Marton, near Middleborough, around 40km away), but the ‘good ships that bore him on his enterprises, brought him glory and left him at rest’ were Whitby ships. The monument’s original inscription, carved in stone, memorialises Captain James Cook and places his memory very squarely in the town of Whitby. On my visit last month, however, what struck me was just how much one can interpret from the existing plaques – all five of them – and thus it is possible to reconstruct a historical biography of memorialisation:

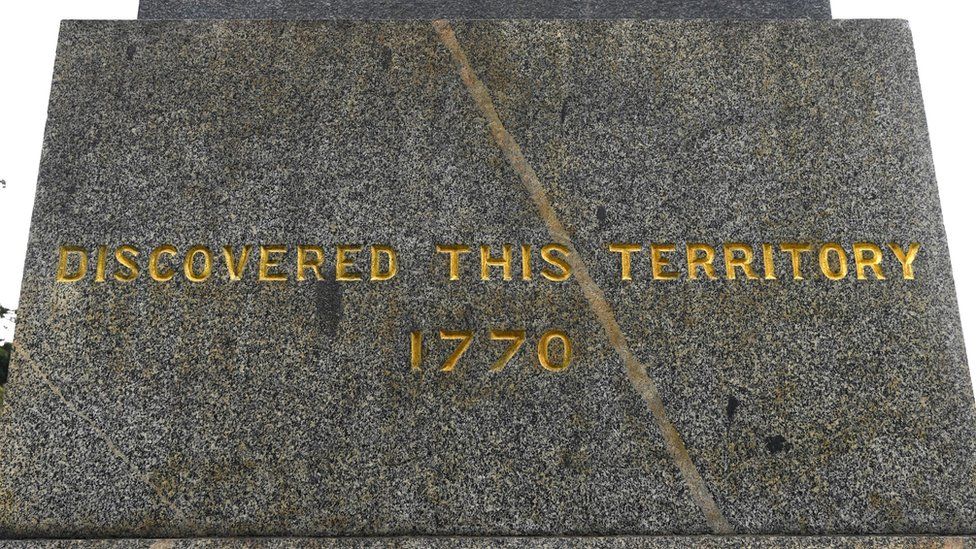

The statue of Captain James Cook is still standing in Whitby, though I would imagine that there are several local and wider debates as to his virtues, and as to whether he should still be standing – or at least whether more explanation (or, perhaps ‘contextualisation’) might be needed, perhaps in the form of an extra plaque (as has happened to JP Coen in the Dutch town of Hoorn). As well as a growing critical literature, these practices have also been increasingly the subject of broader discussion, both supportive and critical, often focussed on whether the subject of the statue (be it Captain Cook or Edward Colston or General Lee) is ‘worthy’ of standing or falling. Highlighting historical atrocities, violence and imperialism, these practices are often a means through which ongoing (neo)colonialism, inequality and exploitation can be challenged. From Rhodes to Colston, via Buller, this Blogsite has hardly been alone in the charting of such practices, which have sought social justice and recognition of the violent and unequal nature of global relations. This style of monument is typical of those that have been subject in recent years to the practice of #Fallism, through which statues are toppled in a history-making endeavour. This is Captain Cook in the familiar guise as the most famous ‘explorer’ of the so-called ‘Age of Exploration’, with the town of Whitby very much staking the claim of being Cook’s ‘home port’. Prominent on the seafront at Whitby, overlooking the entrance to the harbour, is perhaps the most famous statue of the man.

#Captain james cook monument about how to

Recorded and memorialised in several museums, monuments and plaques, as well as a school, a hospital, a railway station, not to mention a vast amount of tourist advertising – of his birthplace, where he went to school, where he lived and learned how to sail (etc.) – this part of Yorkshire is very much the home of Captain James Cook.

On a recent visit to North Yorkshire, I was left in no uncertainty as to the name of one of the region’s most famous sons.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)